Can Humanity Gamble on the Weather? - From Rainfed to Irrigated Agriculture

For all of us who may have forgotten, our food chain starts with photosynthesis. Yes, the process we learned about in elementary school. Everything alive on planet earth depends on the miraculous ability of plants to turn carbon dioxide (CO2), sunlight, and water into carbohydrates (sugar). CO2 comes from the atmosphere, actually, we have too much of it. Light is courtesy of the sun, but water needs to reach the plant's roots either naturally by rain, or artificially by irrigation. Without the constant availability of water, the food-producing machine called a plant works in a suboptimal way or stops working completely. The bottom line, if our crops don’t get a consistent supply of water we will have less food to go around.

How do we feed 10 billion by 2050?

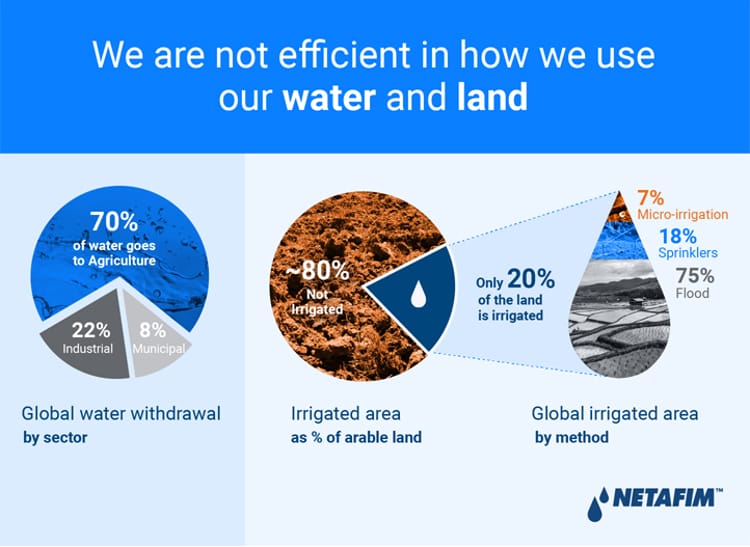

I bet you’ve heard it before; by 2050 there will be almost 10 billion of us living on this planet. Besides huge traffic jams, crowded cities and awful pollution, it also means we’ll need to grow a lot more food. In fact, 70% more. To make this equation work, we will have to produce more on the same amount of land or maybe even on less land. 20 years ago, that might not have been a remarkable problem, and producing more would have simply meant planting more hectares. But things have changed. We have less arable land per capita, limited water resources and on top of it, an unpredictable and changing climate. With so many critical variables out of our control, are we ready to face these food production challenges head-on?

Can we trust the rain with our lives?

The painful answer is no. Rainfed agriculture covers 80% of the world's cultivated land and is responsible for about 60% of crop production. In Sub-Saharan Africa, rainfed cultivation accounts for up to 95% of agriculture. Across the planet, severe droughts and erratic rainfall is the norm. Southern Africa is only now just recovering from six consecutive years of painful drought that took a massive toll on its agricultural sector and especially on the sugar industry. Prolonged heat and dryness during the summer of 2018 had led to drought across many countries in Europe. Rainfed agricultural lands were the first places to suffer. From vineyards to cornfields, yields were severely impacted, resulting in either low yields or complete crop loss.

It's not only about overall rain quantity. Rainfed agriculture is also about timing. It doesn’t help to have massive rainfall if it is not spread out during the crop season. Torrential rain will result in floods and even crop loss, while throughout the rest of the crop growing period, water will not suffice since the soil's water holding capacity is limited. The change in rain patterns across the globe has shone a spotlight on this problem.

On the macro level, the implications of instability in food production go beyond the individual farmer's level. It’s about food security, job security, and economic security, at the personal, regional, and national levels. Can the world afford unstable and suboptimal food production?

Let the facts speak for themselves

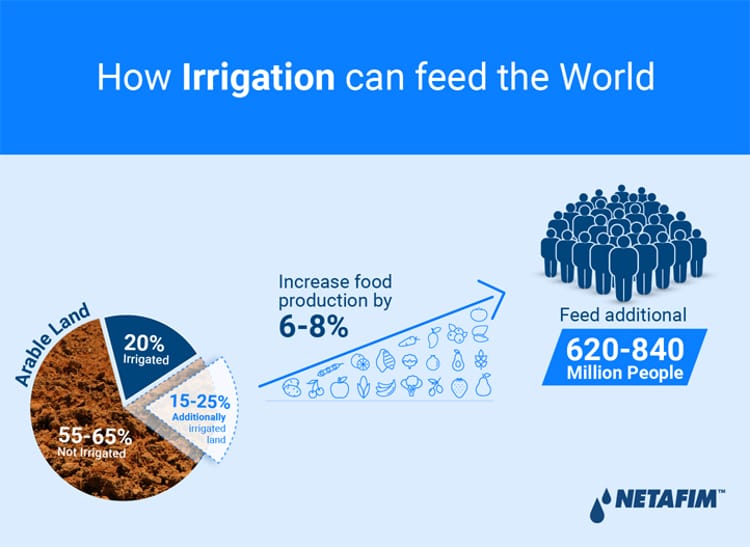

According to recent research from the University of Berkeley California, humanity has an immediate ability to expand irrigation to 15-25% of the rainfed agricultural land increasing our global food production by 6-8%. That will feed an additional 620-840 million people. Irrigation delivers predictability and stability and is the most immediate way we can increase productivity and mitigate risk.

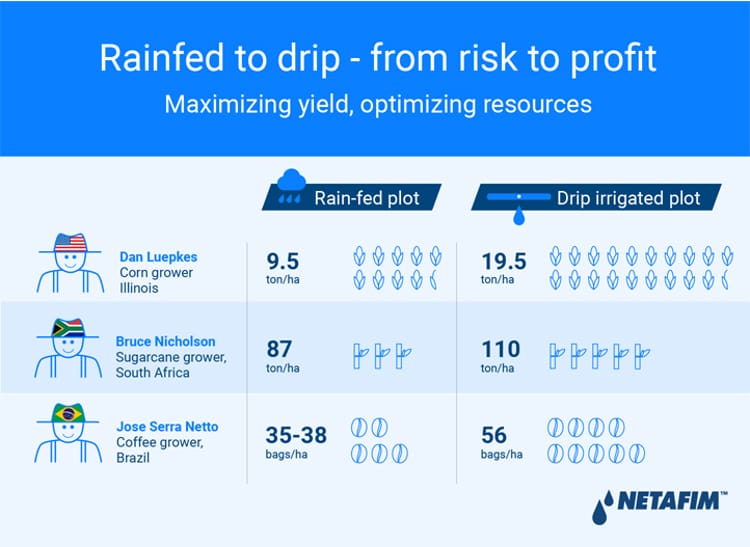

Let’s take for example three farmers in the U.S corn belt who converted some of their corn fields from rainfed to drip irrigation. Dan Luepkes from Illinois used drip successfully to irrigate some of his worst quality lands and was able to maximize income on every hectare. His corn yield grew from 9.5ton/ha on the rain-fed plot to 19.5ton/ha on the drip-irrigated plot. In North Carolina, Kevin Matthews went from 9ton/ha (on a rain-fed plot) to 19ton/ha (on a drip-irrigated plot) and said he “…doubled the yield, but only had to seed one time.” Kelly Garret from Iowa also started using drip irrigation in 2016. He summarized the experience by saying that “You don’t need to buy more land, you don’t need to buy more seeds. Worst-case scenario, you need another truck to haul away the bushels, that’s a wonderful problem!”

For other farmers, the yield is about quality. Rainfed vineyard farming in some of South Africa’s major regions (Stellenbosch and Swartland) was once the norm. Over the last 20 years due to severe droughts, farmers started using some supplementary drip irrigation to ensure the quality, uniformity, and stability of grape production without being dependent on the weather.

In Mindanao, Philippines, thirty years ago, only 20% of the 90,000 hectares of intensively cultivated bananas were irrigated. Growers initially saw irrigation as an insurance policy against dry spells but as those dry spells became longer and more frequent, and buyers demanded specific quality and consistency, farmers began to switch to drip irrigation in large numbers. Today, a massive 50,000 hectares of banana plantations are drip or sprinkler irrigated.

Irrigation is a no brainer, so what holds it back?

Unlike buying other farm machineries such as a tractor or a sprayer, irrigation in many cases requires infrastructural work that is out of the reach of the individual farmer. Most of our food production depends on small and medium-sized farms that lack the financial capabilities of building large water supply networks and rely on local government or other public or private entities for the ability to irrigate. In many countries, governments, water bureaus, and other larger bodies have invested heavily to bring water to the fields and stabilize agriculture and the local economy. Huge investments in countries like India, Peru, Israel, and Turkey are making irrigation feasible to millions of farmers by building the required water delivery infrastructure and allowing subsidies for irrigation equipment. In other countries, the problem remains unsolved and individual farmers remain dependent on rain.

A wake up call

We recently saw how fragile our civilization can be. But did we learn the lesson? Individual farmers can evolve quickly and adapt to change, so we are likely to see increased adoption of irrigation and other technologies on large family and corporate farms. The question is will our leaders who hold the financial key to our food security and socio-economic stability, invest in the resources to switch from rain-dependent agriculture to sustainable, risk-reduced agriculture on a national and global level? I believe that the enhanced focus on food security and economic stability of the farming sector will help to accelerate investment in water and irrigation infrastructure, and will reduce our dependence on rain – for a food-secure future.